Marburg Virus Disease: Risk Factors, Stage, Signs, Symptoms, Causes and Treatment with Homeopathic Medicine

Abstract:

Background: Marburg virus disease is a highly virulent disease that causes haemorrhagic fever, with a fatality ratio of up to 88%. It is in the same family as the virus that causes Ebola virus disease. Two large outbreaks that occurred simultaneously in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany, and in Belgrade, Serbia, in 1967, led to the initial recognition of the disease. The outbreak was associated with laboratory work using African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) imported from Uganda. Subsequently, outbreaks and sporadic cases have been reported in Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Africa (in a person with recent travel history to Zimbabwe) and Uganda. In 2008, two independent cases were reported in travellers who visited a cave inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies in Uganda. Human infection with Marburg virus disease initially results from prolonged exposure to mines or caves inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies. Once an individual is infected with the virus, Marburg can spread through human-to-human transmission via direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and with surfaces and materials (e.g. bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids.

KEYWORDS: Marburg virus, Hemorrhagic fever, Homoeopathy, Clinical features

INRODUCTION:

Marburg virus and Ebola virus are related viruses that may cause hemorrhagic fevers. These are marked by severe bleeding (hemorrhage), organ failure and, in many cases, death. Both viruses are native to Africa, where sporadic outbreaks have occurred for decades. Ebola virus and Marburg virus live in animal hosts. Humans can get the viruses from infected animals. After the initial transmission, the viruses can spread from person to person through contact with body fluids or unclean items such as infected needles. No drug has been approved to treat Ebola virus or Marburg virus. People diagnosed with Ebola virus or Marburg virus receive supportive care and treatment for complications. One vaccine has been approved for Ebola virus. Scientists are studying other vaccines for these deadly diseases.

HISTORY

Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). Thirty-one people became ill, initially laboratory workers followed by several medical personnel and family members who had cared for them. Seven deaths were reported. The first people infected had been exposed to imported African green monkeys or their tissues while conducting research. One additional case was diagnosed retrospectively.

The reservoir host of Marburg virus is the African fruit bat, Rousettus aegyptiacus. Fruit bats infected with Marburg virus do not to show obvious signs of illness. Primates (including humans) can become infected with Marburg virus, and may develop serious disease with high mortality. Further study is needed to determine if other species may also host the virus.

Discovery

Marburg virus was first described in 1967. It was discovered that year during a set of outbreaks of Marburg virus disease in the German cities of Marburg and Frankfurt and the Yugoslav capital Belgrade. Laboratory workers were exposed to tissues of infected grivet monkeys (the African green monkey, Chlorocebus aethiops) at the Behringwerke, a major industrial plant in Marburg which was then part of Hoechst, and later part of CSL Behring. During the outbreaks, thirty-one people became infected and seven of them died.

About Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever

Marburg hemorrhagic fever (Marburg HF) is a rare but severe hemorrhagic fever which affects both humans and non-human primates. Marburg HF is caused by Marburg virus, a genetically unique zoonotic (or, animal-borne) RNA virus of the filovirus family. The five species of Ebola virus are the only other known members of the filovirus family.

Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). Thirty-one people became ill, initially laboratory workers followed by several medical personnel and family members who had cared for them. Seven deaths were reported. The first people infected had been exposed to imported African green monkeys or their tissues while conducting research.

One additional case was diagnosed retrospectively. The reservoir host of Marburg virus is the African fruit bat, Rousettus aegyptiacus. Fruit bats infected with Marburg virus do not to show obvious signs of illness. Primates (including humans) can become infected with Marburg virus, and may develop serious disease with high mortality. Further study is needed to determine if other species may also host the virus.

This Rousettus bat is a sighted, cave-dwelling bat widely distributed across Africa. Given the fruit bat’s wide distribution, more areas are potentially at risk for outbreaks of Marburg HF than previously suspected. The virus is not known to be native to other continents, such as North America. Marburg HF typically appears in sporadic outbreaks throughout Africa; laboratory confirmed cases have been reported in Uganda, Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Angola, and South Africa. Many of the outbreaks started with male mine workers working in bat-infested mines. The virus is then transmitted within their communities through cultural practices, under-protected family care settings, and under-protected health care staff. It is possible that sporadic, isolated cases occur as well, but go unrecognized.

Cases of Marburg HF have occurred outside Africa, such as during the 1967 outbreak, but are infrequent. In 2008, a Dutch tourist developed Marburg HF after returning to the Netherlands from Uganda, and subsequently died. Also in 2008, an American traveler developed Marburg HF after returning to the US from Uganda and recovered. Both travelers had visited a well-known cave inhabited by fruit bats in a national park.

Marburg Outbreaks 2005-2014

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Uganda

On Nov. 13, 2014, the Ministry of Health of Uganda declared Uganda free of Marburg virus External related to the case first reported in early October. Overall, one case was confirmed (fatal) and a total of 197 contacts were followed for 3 weeks. Out of these 197 contacts, 8 developed symptoms similar to Marburg, but all tested negative at the Uganda Virus Research Institute with support from CDC.

Latest CDC Outbreak Information

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Uganda

As of November 29, 2012, the Ugandan Ministry of Health reported 15 confirmed and 8 probable cases of Marburg virus infection, including 15 deaths, in the Kabale, Ibanda, Mbarara, and Kampala Districts of Uganda. Testing of samples by CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch is ongoing at the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Entebbe. Working with the Ministry’s National Task Force, a CDC team is assisting in the diagnostic and epidemiologic aspects of the outbreak. Note that Kabale District, on the border with neighboring Rwanda, is distinct from Kibaale District, the site of the recently-ended Ebola outbreak; both districts are in Uganda’s Western Region.

A recent history of Marburg cases and outbreaks in Uganda includes:

• A fatal case in 2008 of a Dutch tourist who visited the Python Cave, a bat cave in Queen Elizabeth National Park (QENP);

• A non-fatal case in 2008 of an American tourist who visited the same cave in QENP; and,

• A 2007 small outbreak of Marburg HF among miners working in the Kitaka lead and gold mine in Kamwenge District.

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, Imported Case – United States (2008)

On January 22, 2009, CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch retrospectively diagnosed a case of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in a U.S. traveler, who was hospitalized, discharged, and fully recovered. Initial testing of samples collected during the patient’s acute illness in January, 2008 did not initially show evidence of Marburg virus infection. Testing of a convalescent sample indicated a possible previous infection, and more detailed testing of both samples at CDC confirmed that the patient’s illness was due to Marburg hemorrhagic fever.

The recovered patient had visited the “python cave” in Maramagambo Forest, Queen Elizabeth Park, western Uganda. This is a popular destination among tourists to see a cave inhabited by thousands of bats; a fatal case of Marburg hemorrhagic fever occurred in a Dutch tourist in July 2008 who had entered this cave. Both patients likely acquired their infections as a result of contact with cave-dwelling fruit bats, which are capable of harboring Marburg virus. Marburg virus is a zoonotic virus that occurs in tropical areas of Africa, and causes a severe, often fatal, hemorrhagic fever in humans and nonhuman primates. It can also be transmitted through direct contact with a symptomatic patient or materials contaminated with infectious body fluids. The Ugandan Ministry of Health officially closed the cave to visitors in August 2008, after the Dutch case.

The state and local health departments are working with CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch and Traveler’s Health and Animal Importation Branch to further investigate the circumstances of this patient’s case. This includes an assessment of any persons who may have been at risk of exposure at the time the patient was ill, and an investigation of travelers potentially exposed when visiting this or other caves in Africa. There is no evidence of apparent transmission as a result of this case. Travelers should be aware of the risk of acquiring Marburg hemorrhagic fever and other potentially fatal diseases such as rabies after contact with bats.

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, Imported Case – Netherlands ex Uganda, July 2008:

On July 10, 2008 CDC was notified by the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) about a case of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever in a woman from The Netherlands. The woman had recently returned from traveling in Uganda. On one occasion the woman had contact with a bat in a cave in the Maramagambo forest in Western Uganda (at the southern edge of Queen Elizabeth National Park), and became ill after returning to The Netherlands. Laboratory testing at the Bernhard Nocht Institute in Hamburg, Germany revealed evidence of Marburg virus infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The patient died on Thursday July 11, 2008 in the morning.

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Uganda 2007

On July 27, 2007, CDC was notified of a suspect case of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever in Uganda by the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI). A blood specimen taken from the only fatal patient, a miner at a local lead and gold mine, was received by CDC on Friday, July 27, 2007. The specimen tested positive for Marburg virus.

A 6-person CDC team consisting of three medical officers, a mammologist, and two microbiologists arrived in Uganda on August 10, traveling to the town of Ibanda in Kamwenge province, near the site of the mine where the exposures are believed to have occurred. WHO, the Ugandan Ministry of Health, and other collaborators have also deployed personnel. The team has initiated an investigation by capturing bats and other animals at the site of the mine in an effort to further identify the animal host of the Marburg virus, and by tracing human contacts in communities near the mine.

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Angola 2005

On March 25, 2005, CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch reported that testing conducted by its laboratory had identified the presence of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever in 9 of 12 specimens from patients who had died during an outbreak of suspected hemorrhagic fever in Angola. The testing, which was performed using a combination of RT-PCR, antigen-detection ELISAs and virus isolation, was carried out by CDC. The Viral Special Pathogens Branch is a World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Center on Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers.

CDC is working closely with WHO and other international partners to assist the Ministry of Health in Angola with the outbreak investigation and response. A CDC emergency response team consisting of experts in viral hemorrhagic fevers is expected to be deployed to the affected region in the next few days. CDC also has shipped preventive gear and supplies to officials in Angola. Marburg HF Outbreak Distribution Map.

Countries reporting outbreaks of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever

• Angola

• DR Congo

• Germany

• Kenya

• Serbia

• South Africa

• Uganda

Causes

Ebola virus has been found in African monkeys, chimps and other nonhuman primates. A milder strain of Ebola has been discovered in monkeys and pigs in the Philippines. Marburg virus has been found in monkeys, chimps and fruit bats in Africa.

Transmission

African fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) flying outside a cave and observation platform in western Uganda. It is unknown how Marburg virus first transmits from its animal host to humans; however, for the 2 cases in tourists visiting Uganda in 2008, unprotected contact with infected bat feces or aerosols are the most likely routes of infection. After this initial crossover of virus from host animal to humans, transmission occurs through person-to-person contact.

This may happen in several ways: direct contact to droplets of body fluids from infected persons, or contact with equipment and other objects contaminated with infectious blood or tissues. In previous outbreaks, persons who have handled infected non-human primates or have come in direct contact with their fluids or cell cultures have become infected. Spread of the virus between humans has occurred in close environments and direct contacts. A common example is through caregivers in the home or in a hospital (nosocomial transmission).

Transmission from animals to humans

Experts suspect that both viruses spread to humans through an infected animal’s bodily fluids. Examples include:

• Blood: Killing or eating infected animals can spread the viruses. Scientists who have operated on infected animals as part of their research have also caught the virus.

• Waste products: Tourists in certain African caves and some underground mine workers have been infected with the Marburg virus, possibly through contact with the feces or urine of infected bats.

Transmission from person to person

People who have Ebola virus or Marburg virus typically don’t become contagious until they develop symptoms. The viruses can spread through blood, body fluids, or contaminated items such as bedding, clothing or needles. Family members can be infected as they care for sick relatives or prepare the dead for burial. Medical personnel can be infected if they don’t use specialized personal protective equipment that covers them from head to toe. There’s no evidence that Ebola virus or Marburg virus can be spread via insect bites.

Risk of Exposure:

African fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) roosting inside a cave in Uganda. People who have close contact with African fruit bats, humans patients, or non-human primates infected with Marburg virus are at risk. Historically, the people at highest risk include family members and hospital staff who care for patients infected with Marburg virus and have not used proper barrier nursing techniques. Particular occupations, such as veterinarians and laboratory or quarantine facility workers who handle non-human primates from Africa, may also be at increased risk of exposure to Marburg virus. Exposure risk can be higher for travelers visiting endemic regions in Africa, including Uganda and other parts of central Africa, and have contact with fruit bats, or enter caves or mines inhabited by fruit bats.

Risk factors

For most people, the risk of getting Ebola virus or Marburg virus is low. The risk increases if you:

• Travel to Africa. You’re at increased risk if you visit or work in areas where Ebola virus or Marburg virus outbreaks have occurred.

• Conduct animal research. People are more likely to contract the Ebola virus or Marburg virus if they conduct animal research with monkeys imported from Africa or the Philippines.

• Provide medical or personal care. Family members are often infected as they care for sick relatives. Medical personnel also can be infected if they don’t use specialized personal protective equipment that covers them from head to toe.

• Prepare people for burial. The bodies of people who have died of Ebola virus or Marburg virus are still contagious. Helping prepare these bodies for burial can increase your risk of getting the viruses.

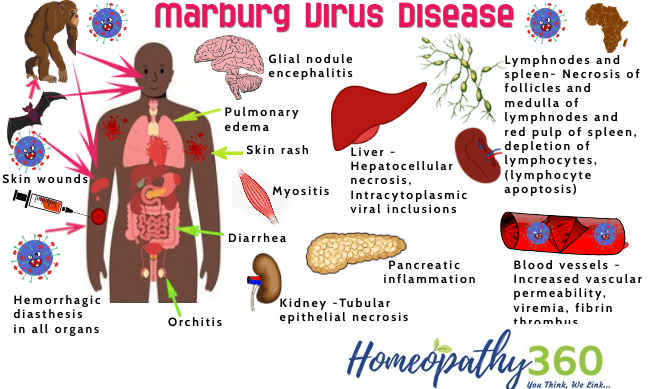

Signs and Symptoms

After an incubation period of 5-10 days, symptom onset is sudden and marked by fever, chills, headache, and myalgia. Around the fifth day after the onset of symptoms, a maculopapular rash, most prominent on the trunk (chest, back, stomach), may occur. Nausea, vomiting, chest pain, a sore throat, abdominal pain, and diarrhea may then appear.

Symptoms become increasingly severe and can include jaundice, inflammation of the pancreas, severe weight loss, delirium, shock, liver failure, massive hemorrhaging, and multi-organ dysfunction. Because many of the signs and symptoms of Marburg hemorrhagic fever are similar to those of other infectious diseases such as malaria or typhoid fever, clinical diagnosis of the disease can be difficult, especially if only a single case is involved. The case-fatality rate for Marburg hemorrhagic fever is between 23-90%.

Ebola hemorrhagic fever

Malaria

Typhoid fever

Leptospirosis

Rickettsial infection

Plague

Bacterial dysentery

Meningococcemia

The differential diagnosis of Marburg’s virus is:

CLINICAL FEATURES:

Signs and symptoms typically begin abruptly within five to 10 days of infection with Ebola virus or Marburg virus. Early signs and symptoms include:

• Fever

• Severe headache

• Joint and muscle aches

• Chills

• Weakness

Over time, symptoms become increasingly severe and may include:

• Nausea and vomiting

• Diarrhea (may be bloody)

• Red eyes

• Raised rash

• Chest pain and cough

• Sore throat

• Stomach pain

• Severe weight loss

• Bruising

• Bleeding, usually from the eyes, and when close to death, possible bleeding from the ears, nose and rectum

• Internal bleeding

Complications

Both Ebola virus and Marburg virus lead to death for a high number of people who are affected. As the illnesses progress, the viruses can cause:

• Multiple organ failure

• Severe bleeding

• Jaundice

• Delirium

• Seizures

• Coma

• Shock

One reason the viruses are so deadly is that they interfere with the immune system’s ability to mount a defense. But scientists don’t understand why some people recover from Ebola virus and Marburg virus and others don’t. For people who survive, recovery is slow. It may take months to regain weight and strength, and the viruses remain in the body for weeks. People may experience:

• Hair loss

• Sensory changes

• Liver inflammation (hepatitis)

• Weakness

• Fatigue

• Headaches

• Eye inflammation

• Testicular inflammation

Diagnosis

Many of the signs and symptoms of Marburg hemorrhagic fever are similar to those of other more frequent infectious diseases, such as malaria or typhoid fever, making diagnosis of the disease difficult. This is especially true if only a single case is involved. However, if a person has the early symptoms of Marburg HF and there is reason to believe that Marburg HF should be considered, the patient should be isolated and public health professionals notified. Samples from the patient can then be collected and tested to confirm infection.

Antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and IgM-capture ELISA can be used to confirm a case of Marburg HF within a few days of symptom onset. Virus isolation may also be performed but should only be done in a high containment laboratory with good laboratory practices. The IgG-capture ELISA is appropriate for testing persons later in the course of disease or after recovery. In deceased patients, immunohistochemistry, virus isolation, or PCR of blood or tissue specimens may be used to diagnose Marburg HF retrospectively. Ebola virus and Marburg virus are difficult to diagnose because early signs and symptoms resemble those of other diseases, such as typhoid and malaria. If doctors suspect that you have Ebola virus or Marburg virus, they use blood tests to quickly identify the virus, including:

• Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

• Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Supportive hospital therapy should be utilized, which includes balancing the patient’s fluids and electrolytes, maintaining oxygen status and blood pressure, replacing lost blood and clotting factors, and treatment for any complicating infections. Experimental treatments are validated in non-human primates models, but have never been tried in humans.

Prevention

Preventive measures against Marburg virus infection are not well defined, as transmission from wildlife to humans remains an area of ongoing research. However, avoiding fruit bats, and sick non-human primates in central Africa, is one way to protect against infection. Measures for prevention of secondary, or person-to-person, transmission are similar to those used for other hemorrhagic fevers. If a patient is either suspected or confirmed to have Marburg hemorrhagic fever, barrier nursing techniques should be used to prevent direct physical contact with the patient. These precautions include wearing of protective gowns, gloves, and masks; placing the infected individual in strict isolation; and sterilization or proper disposal of needles, equipment, and patient excretions.

In conjunction with the World Health Organization, CDC has developed practical, hospital-based guidelines, titled: Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers In the African Health Care Setting. The manual can help health-care facilities recognize cases and prevent further hospital-based disease transmission using locally available materials and few financial resources.

Marburg hemorrhagic fever is a very rare human disease. However, when it occurs, it has the potential to spread to other people, especially health care staff and family members who care for the patient. Therefore, increasing awareness in communities and among health-care providers of the clinical symptoms of patients with Marburg hemorrhagic fever is critical. Better awareness can lead to earlier and stronger precautions against the spread of Marburg virus in both family members and health-care providers. Improving the use of diagnostic tools is another priority. With modern means of transportation that give access even to remote areas, it is possible to obtain rapid testing of samples in disease control centers equipped with Biosafety Level 4 laboratories in order to confirm or rule out Marburg virus infection.

• Avoid areas of known outbreaks. Before traveling to Africa, find out about current epidemics by checking the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

• Wash your hands frequently. As with other infectious diseases, one of the most important preventive measures is frequent hand-washing. Use soap and water, or use alcohol-based hand rubs containing at least 60% alcohol when soap and water aren’t available.

• Avoid bush meat. In developing countries, avoid buying or eating the wild animals, including nonhuman primates, sold in local markets.

• Avoid contact with infected people. In particular, caregivers should avoid contact with an infected person’s body fluids and tissues, including blood, semen, vaginal secretions and saliva. Also avoid the person’s clothing, bedding or other items that may have touched him or her. People with Ebola virus or Marburg virus are most contagious in the later stages of the disease.

• Follow infection-control procedures. If you’re a health care worker, wear specialized personal protective equipment that covers you from head to toe. Keep people who have the viruses isolated from others. Safely throw away needles and sterilize other instruments.

• Don’t handle remains. The bodies of people who have died of Ebola virus or Marburg virus are still contagious. Specially organized and trained teams should bury the remains, using appropriate safety equipment.

Treatment

No antiviral medications have proved effective in treating infection with either Ebola virus or Marburg virus. Supportive hospital care includes:

• Providing fluids

• Maintaining blood pressure

• Providing oxygen as needed

• Replacing lost blood

• Treating other infections that develop

Homoeopathic approach in Marburg Viral disease:

Homeopathy is one of the most popular holistic systems of medicine. The selection of homeopathic medicine for a viral disease is based upon the theory of individualization and symptoms similarity by using holistic approach. This is the only way through which a state of complete health can be regained by removing all the sign and symptoms from which the patient is suffering. The aim of homeopathic medicine for Marburg viral disease is not only to treat hemorrhage but to address its underlying cause and individual susceptibility. As far as therapeutic medication is concerned, several remedies are available to treat viral disease that can be selected on the basis of cause, sensations and modalities of the complaints. For individualized remedy selection and treatment, the patient should consult a qualified homeopathic doctor in person. There are following remedies which are helpful in the treatment for viral diseases.

FEVER STAGE

Arsenicum album

A person who needs this remedy during flu feels chilly and exhausted, along with an anxious restlessness. The person may be thirsty, but often only takes small sips. If the digestive system is involved, nausea with burning pain, or vomiting and acrid diarrhea may occur. If the flu is respiratory, a watery, runny nose with sneezing paroxysms and a dry or wheezing cough are often seen. The person’s head usually feels hot, while the rest of the body is chilly.

Belladonna

This remedy relieves high fever of sudden onset with profuse sweating, and hypersensitivity to light and noise.

Bryonia alba

This relieves high fever with body aches improved by staying immobile.

Eupatorium perfoliatum

This remedy relieves bone pains and body aches associated with flu and severe colds.

Ferrum phosphoricum

This relieves low-grade fever with weakness and tendency to nosebleeds and earaches.

Gelsemium

This remedy relieves flu-like symptoms with fever, headache, dizziness and general weakness.

Nux vomica

When this remedy is indicated in influenza, the person may have have high fever, violent chills, strong nausea and cramping in the digestive tract (or a painful cough and constricted breathing if the flu is respiratory). Headache usually occurs, along with oversensitivity to sound, bright light, and odors. A person who needs Nux vomica is often very irritable, feeling worse from exertion and worse from being cold in any way.

Oscillococcinum

This remedy relieve flu-like symptoms: feeling run down, body aches, chills and fever.

Rhus toxicodendron

This remedy relieves fever with restlessness: The patient is continuously moving to find a comfortable position and relieve the body aches.

Other Remedies

Aconitum napellus

This remedy relieves high fever of sudden onset, with a hot face and dry skin. <

Apis mellifica

This remedy may be helpful if a person has dry fever that alternates with sweating, facial flushing, and a very sore throat with swollen tonsils. Pain may extend to the ears, and the eyelids may be swollen. Exposure to cool air and cold applications may bring relief. Despite the fever, thirst usually is low. The person can be very irritable, disliking interference.

Phosphorus

When this remedy is needed during flu, the person has a fever with an easily-flushing face, and feels very weak and dizzy. Headache, hoarseness, sore throat, and cough are likely. If the focus is digestive, stomach pain and nausea or vomiting usually occur. A person who needs this remedy often has a strong anxiety, wanting others to be around to offer company and reassurance. Strong thirst, with a tendency to vomit when liquids warm up in the stomach, is a strong indication for Phosphorus.

Sulphur

This remedy may be useful if a flu is very long-lasting or has some lingering symptoms—often after people have neglected to take good care of themselves. Symptoms, either digestive or respiratory, will often have a hot or burning quality. The person may feel hot and sweaty, with low fever and reddish mucous membranes. Heat aggravates the symptoms, and the person often feels worse after bathing.

The following medicines are indicated for bleeding:

Aconitum: Give this medicine when there is bleeding with marked restlessness, fear and anxiety. Give 30 or 200 potency every 15 minutes or until bleeding stops.

Arnica: This is very effective for bleeding whether external or internal and is appropriate also for the shock and trauma that is present along with bleeding. Give Arnica 30 every 15 mins to stop the flow or Arnica 200 until flow stops.

Hamamelis: When a cut or wound is bleeding profusely, give Hamamelis as (like Arnica) it can stop bleeding fast. Ideal for profuse nosebleeds. Can also be used for bleeding haemorrhoids. Use the 30th potency every 15-30 minutes until bleeding has stopped.

Ipecac: Use Ipecac if there are repeated nosebleeds or if there is bleeding of any kind accompanied by faintness, nausea or air hunger (the patient may gulp or gasp). Give Ipecac 30 every 15-30 mins until patient recovers and bleeding stops.

Phosphorus: For frequent nosebleeds especially in children or for dental haemorrhage. Use in 30th potency every 15-20 mins until bleeding subsides.

Belladonna : blood hot , throbbing carotids , congestion to head .

Carbo veg : Almost entire collapse , pale face , wants to be fanned .

China : Great loss of blood , ringing in ears , faintness.

Crotalus : blood clots , in long dark strings .

Ferrum Phos : partly fluid , partly solid , very red face or red and pale alternately .

Hyoscyamus : delirium and jerking and twitching of muscles .

Lachesis : blood decomposed , sediment like charred straw .

Crotalus, Elaps, sulphuric acid black fluid blood ;the first and the last from all out lets .

Nitric acid : active haemorrhages of bright blood .

Phosphorus : profuse and persistent , even from small wounds and tumors .

Platinum : partly fluid and partly hard black clots .

Pulsatilla : Intermittent haemorrhages .

Secale cor : passive flow in feeble ,cachectic women Sulphur : in psoric constitutions ; other remedies falling and indications might be added here but haemorrhages is only one symptom and never alone furnishes a reliable indication for any one remedy but ipecacuanha is one of the best if indicated.

Following are homoeopathic medicine for treatment divided in two parts:

1. Homoeopathic medicine in Marburg outburst free area:

Marburg Virus Obsession

Fear spreading around other countries too which itself bringing down the immunity of the people for which ACONITE CM can be given to counteract the effects development due to fear.

2. Homoeopathic Medicines in Marburg Outbreak:

• CROTALUS HORRIDUS is a homeopathic cure for Marburg Virus at 30C dilution according to reliable sources.

• As a preventative if an outbreak happens nearby, Crotalus horridus 30C, one dose daily, until the threat is out of the area is the method.

• If a person is infected, the remedies most commonly used would be the following.

• One dose every hour, but as the severity of the symptoms decrease, frequency is reduced. If no improvement is seen after 6 doses, a new remedy ought to be considered.

• Crotalus horridus 30C – Is to be considered for when there is difficulty swallowing due to spasms and constriction of the throat, dark purplish blood, edema with purplish, mottled skin.

• Bothrops 30C – Is the remedy to think of when nervous trembling, difficulty articulating speech, sluggishness, swollen puffy face, black vomiting are present

• Lachesis mutus 30C ,– when there’s delirium with trembling and confusion, haemorrhage in any area, consider this remedy. Often, the person cannot bear tight or constricting clothing or bandages and feels better from heat and worse on the leftside

Conclusion

The emergence of these above named dreaded diseases swallowed mankind in past or recently and many no. of other rain forest agents appears consequence of the ruin of tropical biosphere. The emerging viruses are surfacing from ecologically damaged parts of the earth. In a sense, the earth is mounting an immune response against human species. It is beginning to react to the human parasite. The overall cure shall be to plan public health as global health ecologically. Man is not centre of web of world but a strand. If rest of the web exist man will exist.

References

o Adjemian J, Farnon EC, Tschioko F, et al. Outbreak of Marburg hemorrhagic fever among miners in Kamwenge and Ibanda districts, Uganda, 2007. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S796-S799.

o Amman BR, Carroll SA, Reed ZD, et al. Seasonal pulses of Marburg virus circulation in juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus bats coincide with periods of increased risk of human iInfection. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8(10):e1002877.

o Bausch DG, Borchert M, Grein T, et al. Risk Factors for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9(12):1531-1537.

o Bausch DG , Geisbert TW. Development of vaccines for Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2007;6(1):57-74.

o Bausch DG, Nichol ST, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, et al. Marburg hemorrhagic fever associated with multiple genetic Lineages of virus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:9099-19.

o Bausch DG, Sprecher AG, Jeffs B, et al. Treatment of Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers: A strategy for testing new drugs and vaccines under outbreak conditions. Antiviral Research. 2008;78(1):150-161.

o Brauburger K, Hume AJ, Muhlberger E, et al. Forty-five years of Marburg virus research. Viruses. 2012;4(10):1878-1927.

o Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Imported case of Marburg hemorrhagic fever – Colorado, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(49):1377-1381.

o Gear JHS. Haemorrhagic fevers of Africa: an account of two recent outbreaks. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 1977;48(1):5-8.

o Geisbert TW, Bausch DG, Feldmann H. Prospects for immunisation against Marburg and Ebola viruses. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2010;20(6):344-357.

o Hensley LE, Alves DA, Geisbert JB, et al. TW. Pathogenesis of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S1021-S1031.

o Johnson ED, Johnson BK, Silverstein D, et al. Characterization of a new Marburg virus isolated from a 1987 fatal case in Kenya. Archives of Virology. 1996;11(Suppl):101-114.

o Kortepeter MG, Bausch DG, Bray M. Basic clinical and laboratory features of filoviral hemorrhagic fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S810-S816.

o MacNeil A, Rollin PE. Ebola and Marburg Hemorrhagic Fevers: Neglected Tropical Diseases? PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6(6):e1546.

o Martini GA, Knauff HG, Schmidt HA, et al. A hitherto unknown infectious disease contracted from monkeys. “Marburgvirus” disease. German Medical Monthly. 1968;13(10):457-470.

o Mehedi M, Groseth A, Feldmann H, et al. Clinical aspects of Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Future Virology 2011;6(9):1091- 1106.

o Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Zaki S, et al. Arenaviruses and filoviruses. In: Versalovic J, Carroll KC, Funke G, et al., eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2011. 2. pp. 1514-1529.

o Smith LM, Hensley LE, Geisbert TW, et al. Interferon-beta therapy prolongs survival in rhesus macaque models of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;208(2):310-318.

o Swanepoel R, Smit SB, Rollin PE, et al. Studies of reservoir hosts for Marburg virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(12):1847-1851.

o Teepe RG, Johnson BK, Ocheng D, et al. A probable case of Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever in Kenya. East African Medical Journal. 1983;60(10):718-722.

o Towner JS, Amman BR, Sealy TK, et al. Isolation of genetically diverse Marburg viruses from Egyptian fruit bats. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(7):e1000536.

o Towner JS , Khristova ML, Sealy TK, et al. Marburgvirus genomics and association with a large hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Angola. Journal of Virology. 2006; 80(13):6497-516.

o Warren TK , Warfield KL, Wells J, et al. Advanced antisense therapies for postexposure protection against lethal filovirus infections. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(9):991-994.

https://www.who.int/csr/disease/marburg/Marburg-fact-sheet-EN-20-Oct-2017.pdf

(a) Siegert R. Marburg Virus. In. Virology Monongraph. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1972; pp. 98- 153.

Feldmann, H., W. Slenczka, and H. D. Klenk. 1996. Emerging and reemerging of filoviruses. Arch. Virol. 11(Suppl.):77-100.

World Health Organization. Marburg virus disease: South Africa. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 1975; 50(12):124-125.

Smith DH, Johnson BK, Isaacson M, et al. Marburg –virus disease in Kenya. Lancet. 1982; 1(8276):816-820.

Johnson ED, Johnson BK, Silverstein D, et al. Characterization of a new Marburg virus isolated from a 1987 fatal case in Kenya. Arch. Virol. 1996; 11(Suppl):101-114. 5. Bausch DG, Nichol ST, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, et al. Marburg hemorrhagic fever associated with multiple genetic lineages of virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006; 355:909-919.

Towner JS, Khristova ML, Sealy TK, et al. Marburgvirus genomics and associated with a loarge hemorrhaig fever outbreak in Angola. J. Virol. 2006; 80(13):6497-6516.

World Health Organization. Marburg haemorrhagic fever, Uganda. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2007; 82(33):297-298.

World Health Organization. Case of Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever Imported into the Netherlands from Uganda. 10 July 2008. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2008_07_10/en/index.html

Timen A, Koopmans M, Vossen A, et al. Response to Imported Case of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009; 15(8).

HOMOEOPATHIC MATERIA MEDICA by William BOERICKE, M.D.

Materia Medica by James Tyler Kent

Repertory of Hering’s Guiding Symptoms of our Materia medica.

Ananthanarayan and Paniker’s Textbook of Microbiology.

About Author:

Dr DON J SCOTT BERIN G BHMS [M D] PG Scholar

WHITE MEMORIAL HOMOEOPATHIC MEDICAL COLLEGE , VEEYANOOR, ATTOOR, KK DIST, TAMILNADU, SOUTH INDIA.

ORCID ID : 0000-0002-5636-2794

EMAIL: [email protected]